From Sustainability By Numbers

Bird species are under threat from climate change.

It would be worrying, then, if a move to low-carbon energy increased pressures on bird populations. That’s a common concern as countries move to wind power.

It’s true: wind turbines do kill birds (and bats). But how many, and are they a bigger threat than other hazards?

In this post, I take a look at estimates of bird deaths from turbines and try to put them in context. I also explore ways that we can reduce them.

How many birds do wind turbines kill?

Measuring bird kills from turbines is hard. An obvious way to do so is to have humans go out and count bird carcasses in the area. Many studies have done that.

The problem is that humans often miss small birds, such as songbirds. That’s where dog searches come in.

The estimates that I found in the literature vary quite a bit. Partly due to measurement challenges, but also because risks vary by location: some areas will be prime hotspots for wildlife while others will be more barren.

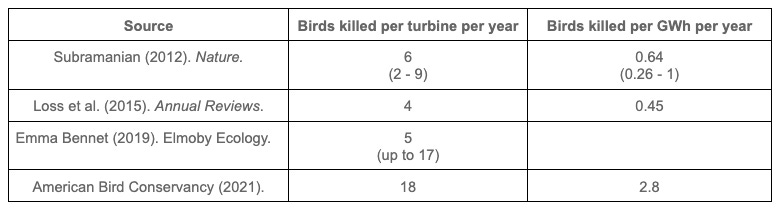

Estimates ranged from 4 to 18 birds killed per turbine per year. More than four times the difference. I’ve detailed some of these studies in the table below.1

Sources: Subramanian (2012); Loss et al. (2015); Emma Bennet (2019); American Bird Conservancy (2021).

The large spread of these estimates isn’t very satisfying, but at least gives us some sense of magnitude. What would this mean for the total number of birds killed each year?

Let’s apply these numbers to the United States (which is where most of the studies came from).

In 2022, the US produced 434 TWh of wind power.2 Taking the numbers above, that gives us a range of 200,000 to 1.2 million. The upper figure seems more likely since it tries to correct for the under-detection of smaller birds. Let’s call it around one million birds per year.

Assume that these risks are the same across the world, and global deaths are probably over 5 million.3

Cats, buildings, and cars kill far more birds than wind power

Around one million birds are killed in the US. Is that a big number?

Not really, compared to other pressures.

The chart below shows estimates of the number of birds killed by different hazards in the US.

You can see that wind turbines kill a few million at most. Cars, buildings, and pesticides kill tens to hundreds of millions each. Cats kill at least a billion.

Do these figures seem credible? I did a bit of a sense check on a few of the numbers below. If you want to follow along, feel free. If not, skip to the next section.

[see the article for detailed discussion of the data. The author also discusses how any birds are being and will be killed by climate change, and concludes that the data are unreliable.]

Wind power is a threat to particular types of birds, particularly birds of prey

It’s not just the total amount of birds that are killed that matters, but what types. If a particular species of bird is disproportionately affected it could have real impacts on population dynamics and risk of extinction.

A study by Chris Thaxter and colleagues (2017) looked at the collision rates of different bird species from a large literature review. [See chart in original text]

In short, birds of prey such as eagles, raptors, and hawks; shorebirds; and storklike orders are at much higher risk of collisions than other families, such as songbirds. This disproportionate risk has been found across many other studies.

These species can be at a higher risk for several reasons. First, they will often use ridgetops to get lift from the wind. Incidentally, this is also a good spot for wind turbines. Second, they are often migratory birds; if wind farms are in their migratory route this puts them at higher risk. More indirect impacts of wind farms – which might not be reflected in death statistics – is their effect on the disruption of migratory patterns.

While the total number of birds killed by turbines is low compared to other hazards, the threat to particular species is more concerning. We need better mapping of key hotspots for these species so that wind farms can be deployed in suitable locations. More on how we can reduce these deaths later.

Wind power is probably a bigger threat to bats

I’ve mostly focused on bird fatalities, but wind power also kills bats. I found it harder to get good numbers here, but estimates suggest it’s in the range of 6 to 20 bats per turbine per year. Some estimates are even higher.

The Thaxter et al. (2017) paper that we just looked at also measured collision rates among bats. If you look at the scale of the ‘collisions/turbines/year’ you’ll see that it’s an order of magnitude higher.

Again, this tallies with other research that suggests that bats have higher mortality rates than birds for wind farm collisions.

We can reduce bird and bat deaths from wind power

We’re not completely helpless in this dilemma. There’s a lot that we can do to limit the biodiversity impact of wind farms, even if fatality rates are not reduced to zero.4

Here’s what we can do:

1. Turn off wind turbines at very low speeds when bats are around

Bats tend to get hit by wind turbines when wind speeds are very low. They struggle to fly in windier conditions. That means we can prevent a lot of bat deaths by curtailing – switching off – our turbines when there isn’t much wind.

You might think that this would hinder energy supply and eat into owner profits. But studies suggest it doesn’t make much difference.

A study from Pennsylvania reduced bat deaths by 44% when wind turbines were turned on at 5, rather than 3.5 metres per second.5 And they fell by 93% when this was increased to 6.5 metres per second.

A study in Australia found that raising the wind speed threshold from 3 to 4.5 metres per second reduced deaths by 54%, and the wind farm only lost 0.1% of revenue.6

Another study in Cadiz, in Spain, found that bird deaths were halved with only a 0.07% loss in energy production. That’s because the biggest risk was migratory birds – which pass through very occasionally. Shutting down production during this time was quick and saved many lives.

2. Don’t put wind farms in high-risk areas for birds and bats

Areas like ridgetops are prime spots for migratory birds and raptors that use the winds for uplift.

As we saw earlier, these species tend to be disproportionately affected by wind farms, so we should strive to avoid these areas.

3. Fewer larger turbines are better than many small ones

Birds and bats might be more likely to collide with a large turbine than a small one. But the question is whether a wind farm should have a few large turbines or lots of small ones.

The study by Thaxter et al. (2017) suggests the former. Fatality rates for both birds and bats tend to be higher in wind farms with turbines of very low capacity.

Having a small number of large turbines would therefore reduce fatality rates.

4. Paint the turbines black

When birds get close to turbines, the blades spin so quickly that it blurs their vision. But, if you paint the turbines black, it makes them much more visible.

Some tests of this approach in Norway reduced bird deaths by more than 70%.7

It might not be as effective for offshore farms, so that still needs to be tested.

5. Play alert noises to bats and birds to deter them

For some bat species, playing high-pitch sounds (which humans can’t hear) can deter them from the area. A study in Texas reduced the deaths of the deaths of two species of bats by 54% and 78%.8 It was then rolled out to many wind farms in the area.

Other systems can be used to identify eagles in the nearby area, and either emit distracting noises or switch the turbines off automatically.

6. Use GPS to track and find the optimal height for turbines

Surveillance technologies, such as GPS, can help scientists understand the flying patterns of migratory species. That means we can pick more optimal heights for turbines when they’re being constructed.

It can also alert wind farm generators that migratory flocks are in the area, so they can switch turbines off during high-risk times.

While some wildlife deaths from wind power might be unavoidable, there’s a lot that we can do to reduce them. It might come at very little cost to energy output and profit, so at a time when the world’s birds are under threat, it’s worth doing.

[Read more here]

No comments:

Post a Comment