From EMBER

Putin’s energy blackmail has left the EU with few options. Had renewable energy capacity been rapidly expanded, Europe would not need coal to keep the lights on.

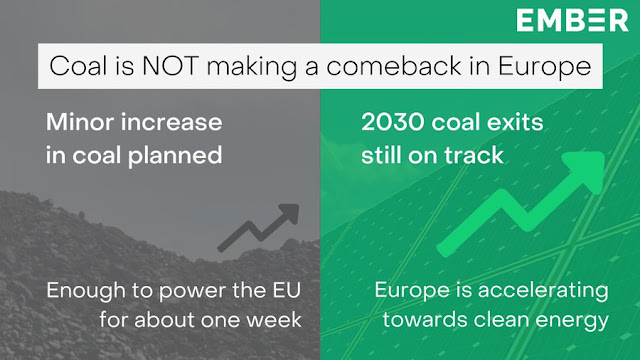

Germany, Austria, France and the Netherlands have recently announced plans to enable increased coal power generation in the event that Russian gas supplies suddenly stop. This would allow gas that was being used for electricity production to be diverted elsewhere, in particular into gas storage facilities so they can reach the required 90% full levels by November.

In total, 13.5 GW of coal-fired plants will be placed on stand-by in supply reserve facilities, adding 12% to the EU’s existing coal fleet (109 GW) and only 1.5% to its total installed power generation capacity (920 GW).

The use of coal is only a last resort, short term measure, with consensus in Europe that the only way to extricate itself from cost and security crises is to get off fossil fuels. Germany remains firmly committed to its coal exit plan. The government has reiterated, “the coal exit in 2030 isn’t wobbling at all. It is more important than ever that it happens in 2030.” The Netherlands is not amending its 2029 coal phase-out date. France is only allowing Emile Huchet to be in reserve for this winter. And Austria has clearly stated that the Mellach plant is coming out of retirement “so that in an emergency it can once again produce electricity from coal (not gas)”.

These temporary measures will only result in increased coal burning if Russia cuts gas supply further. If this does not happen the coal plants will not come back online. If all the plants do operate and run at 65% of their 13.5 GW capacity, it would result in 60 TWh of additional coal power generation in 2023. This equates to 14% of 2021 EU coal electricity production and 2% of 2021 EU total electricity production. From a climate perspective, the net additional CO2 emissions in 2023 would be approximately 30 million tonnes, representing 4% of 2021 EU power sector emissions and 1.3% of total 2021 EU CO2 emissions. So while it would be preferable to avoid any increase in emissions, the temporary uptick will not derail the EU’s longer-term climate goals.

The current crisis has acted as a catalyst for an accelerated European clean energy transition. Fossil gas is no longer viewed as a viable transition fuel and instead Europe is implementing a much faster transition away from both coal and gas.

In May, the European Commission published its updated REPowerEU communication. In those plans, it had already incorporated an increase in coal power (+105 TWh) and falling gas power (-240 TWh) without derailing EU climate objectives.

“Despite temporarily higher coal use in power generation, the climate ambition levels are reached since REPowerEU leads to investments in renewables and energy efficiency beyond the Fit for 55 proposals.”

The proposals include a massive ramp-up in wind and solar deployment, with renewables accounting for 69% of electricity production by 2030. And a recent Ember report shows that nineteen European governments have accelerated their decarbonisation in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, gas crisis and Russia’s aggression.

No comments:

Post a Comment